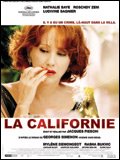

La Californie: Hollywood's black beast lives on the Côte d'Azur

My general preference for French cinema over American cinema stems from my desire to see women and men free to roam outside structure, to be transported out of the niches they are placed in our society which is far from being progressive.

My general preference for French cinema over American cinema stems from my desire to see women and men free to roam outside structure, to be transported out of the niches they are placed in our society which is far from being progressive.And the middle-aged woman is the bête noire of Hollywood films. Women of a certain age are often portrayed as neurotic, sexually and emotionally desperate and somehow dirty so that male viewers hold them in contempt, young women snigger, thirty-something women quake in sagging boots, and middle-aged women feel indignant at their beastly reflection in this distorted, carnivale mirror. French films are much more likely to portray middle-aged women in strong, sexy roles that make both men and women dream.

This even goes down to something as core as lighting. In mainstream, American cinema if a middle-aged woman must be shown as anything but pathos-evoking (or "just a mother"), she is likely to be shown in soft wrinkle-erasing light, the scars of life are removed so that she appears ageless.

But in France, when it comes to celebrities, the French aren't as prone to prostrate themselves before the altar of youth. Being in the limelight in France means showing wrinkles as a celebration of life and not erasing all traces that you have lived for longer than twenty years. Here, in the magazines devoted to celebrities, they will put one of their older actresses, wrinkles and all, on the cover. No question of photoshopping. Because that's how it is, you get older, you get wrinkles but it does not mean that you are washed up, you are still beautiful and celebrated.

Oh sure, you see wrinkles in English-speaking nations' magazines as well, but it's not `by the way she has wrinkles', usually it is in a special about wrinkles and offers tips on the kind of injection she (I say she because adherence to the cult of youth is primarily thrust upon women) should get to decrease these. It's merely so we can all have a good cackle at her for not being perfect.

In so many Hollywood films if you are passed the "age of consent", to use the Japanese expression: you are christmas cake, starting to crumble, and by default you must be neurotic and feeble.

That’s why I was disappointed with Jacques Fieschi's La Californie. Although the title of the film was chosen for other reasons, I think it was aptly named in the sense that this film was closer to Hollywood-style than your average French film.

Maguy (played by Nathalie Baye) is soaking rich, in her fifties, whiling away very long days in her huge house on the Côte d'Azur with an eclectic mix of friendly parasites: her personal hairdresser (gay ofcourse: it was beyond the limits of this film to have a male hairdresser who isn’t gay or a gay, male hairdresser who doesn't like going to night clubs and "making parties", or for example, to include a role for a gay butcher) and his boyfriend, her drinking buddy Katia (Mylène Demongeot) and two strapping lads -Mirko (Roschdy Zem) and Stefan (Radivoje Bukvic) best friends who escaped their country “in the east” after the crash of communism and now operate as chore-boys and gigolos for Maguy.

The story begins with the arrival of Maguy’s daughter Hélène who she hasn’t seen for ten years (Ludivine Sagnier always to be applauded with feet and hands for her versatile roles) who wants to borrow money from her mother to start a business venture - an independent book printing shop in Paris.

Hélène and Stefan promptly fall in love, leaving us to flinch as Mirko, the third wheel, froths with violent jealousy and dissatisfaction with his own impotent and useless life, and just as promptly as it began, destroys the relationship between Stefan and Hélène.

Maguy, pattering about her home wearing tailored African cottons, caught up in endless petty squabbles as the household chokes on the fumes of ennui and alcohol, is clingy and needy when it comes to Mirko - trying to control him through her money (that old idea that nothing in a middle-aged woman could attract a younger man - and hey, mirko's not that young - except money).

Other characters in the film hold her in contempt. Her daughter calls her mother a "pute" when Stefan admits he slept with her several times and even Mirko himself refers to her as a prostitute. Correctly speaking money did change hands, but when calling names it's probably best to remember who was paying who for sex. At one point Mirko refers to her as "dirty" and that he doesn't know how he can keep having sex with her, this old notion that middle-aged woman must quash their libidos (or else cop a load of abuse) and resign themselves to the fact that they smell like mothballs and polyester sweat and are therefore completely unattractive to even the ugliest of men.

Right up to the violent end of the film Maguy is portrayed as hysterical and ridiculous and we can't help feeling that beyond a certain age her life was a pointless exercise: best just to cover her with a drab blanket and forget about her and check out what's happening with the young people. Mirko's "suicide" in a dark street at the hands of the mafia seemed somehow heroic, compared to Maguy's domestic murder in the soft lighting of a home she rarely left whilst in the middle of a hissy fit - what are they trying to tell us? it was all for the best?

<< Home